The FITT principle stands as one of the most scientifically validated frameworks for designing exercise programs that deliver measurable health benefits. Whether you’re embarking on your first fitness journey, recovering from a sedentary lifestyle, or seeking to optimize an existing routine, understanding and applying this systematic approach can transform your relationship with physical activity[1]. Research consistently demonstrates that structured exercise programs following the FITT principle framework[2] produce superior outcomes compared to unstructured approaches, with benefits ranging from improved cardiovascular health and metabolic function to enhanced mental well-being and reduced chronic disease risk.

Understanding the FITT Principle Framework

The FITT acronym[3] represents four fundamental components that collectively define any exercise program: Frequency (how often you exercise), Intensity (how hard you work), Time (duration of each session), and Type (the kind of activities performed). This deceptively simple framework provides remarkable flexibility, allowing customization for individuals across all fitness levels, age groups, and health conditions. The genius of the FITT principle lies in its systematic approach[4]—by manipulating one or more of these variables, you can progressively challenge your body, promote physiological adaptations, and achieve specific fitness goals while minimizing injury risk[5].

The Science Behind Each FITT Principle Component

Frequency: Establishing Your Exercise Rhythm

Frequency addresses the fundamental question of how often you should engage in physical activity. For cardiovascular fitness[6], research supports a minimum of three sessions per week for beginners, progressing to five or six sessions for those pursuing more ambitious goals. The American College of Sports Medicine[7] recommends at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise weekly, which can be distributed across multiple days according to individual schedules and preferences.[2]

Strength training frequency follows different guidelines, as muscles require adequate recovery time between sessions targeting the same muscle groups. The evidence-based recommendation suggests two to three resistance training sessions per week, with at least one day of rest between workouts focusing on identical muscle groups. This recovery period allows muscle fibers to repair and strengthen, a process essential for building strength and avoiding overtraining syndrome.[8]

For beginners, starting with lower frequency and gradually increasing as fitness improves represents the safest approach. One landmark study found that individuals who started with just two to three exercise sessions per week and systematically increased frequency demonstrated better long-term adherence compared to those who immediately adopted aggressive schedules. The principle of progressive adaptation[9] applies here—your body needs time to adjust to new demands before you increase the training load.[9]

Intensity: Calibrating Your Effort Level

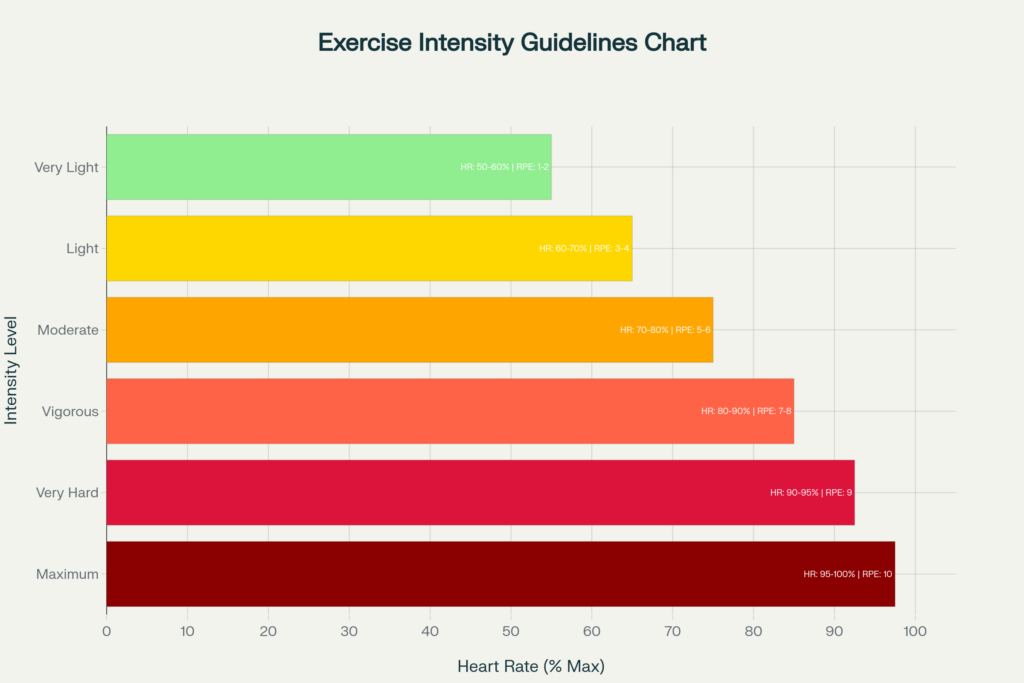

Intensity measures how hard your body works during exercise and represents perhaps the most critical yet challenging component to monitor accurately. Multiple methods exist for gauging intensity[10], each with distinct advantages. Heart rate monitoring provides objective data, with target zones typically calculated as percentages of maximum heart rate. The standard formula estimates maximum heart rate as 220 minus your age[11], though more accurate formulas exist, such as 208 minus (0.7 × age), which research suggests provides better precision across diverse populations.

For moderate-intensity aerobic exercise, target heart rates generally fall between 50-70% of maximum heart rate, while vigorous-intensity exercise elevates the heart rate to 70-85% of maximum. These zones correspond to different physiological benefits—moderate intensity enhances endurance and fat metabolism, while vigorous intensity improves cardiovascular capacity and lactate threshold.[8]

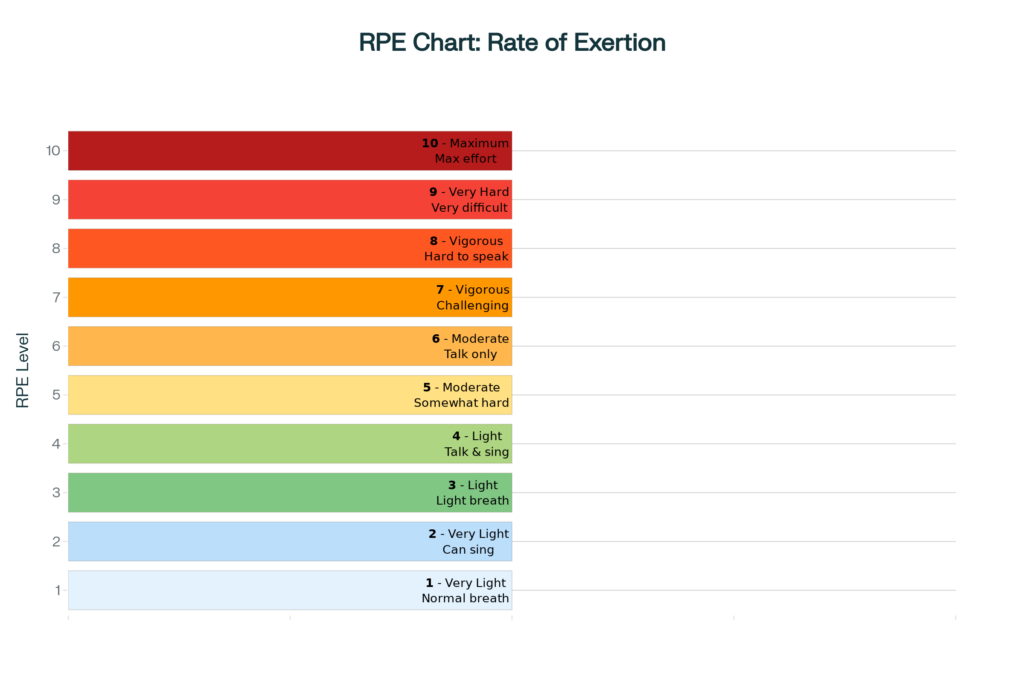

The Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale[12] offers a subjective but highly practical alternative, particularly for individuals without heart rate monitors or those taking medications that affect heart rate. Using a scale from 1 to 10, moderate intensity corresponds to a rating of 5-6, where you can maintain conversation but breathing becomes noticeably heavier, while vigorous intensity rates 7-8, characterized by difficulty speaking in complete sentences. Research demonstrates strong correlations between RPE ratings and physiological markers, validating this method as a reliable intensity gauge.[2]

For resistance training, intensity relates to the weight lifted relative to your one-repetition maximum (1-RM). Beginners should start with 60-70% of their 1-RM, performing higher repetitions (12-15) with lighter weights to build muscular endurance and proper form. As strength develops, increasing weight to 70-80% of 1-RM with moderate repetitions (8-12) optimizes hypertrophy and overall strength gains.

[4]Time: Determining Optimal Duration

The time component addresses how long each exercise session should last, with recommendations varying based on the type of exercise and its intensity. For aerobic exercise, the consensus from major health organizations suggests a minimum of 30 minutes per session for moderate-intensity activities, or 20-30 minutes for vigorous-intensity exercise. However, these durations represent minimums—individuals targeting weight loss or enhanced fitness may benefit from extending sessions to 45-60 minutes.[2]

An important consideration often overlooked is that exercise time can be accumulated throughout the day. Research demonstrates that three 10-minute bouts of activity produce similar cardiovascular benefits to one continuous 30-minute session, making exercise more accessible for individuals with limited time availability. This flexibility dramatically reduces barriers to participation and can significantly improve long-term adherence.

Resistance training sessions typically span 45-75 minutes, including warm-up and cool-down periods. The actual working time depends on the number of exercises (typically 7-10 targeting major muscle groups), sets (2-3 for most individuals), and repetitions per set. Rest intervals between sets also contribute to total session time—moderate-intensity strength training typically incorporates 1-2 minute rest periods, while higher-intensity lifting may require 2-3 minutes for adequate recovery.[4]

Flexibility training[13], though often neglected, should occupy 10-15 minutes per session, with each major muscle group stretched for 30-60 seconds. Integrating flexibility work into cool-down periods provides an efficient approach to ensure adequate stretching without extending total workout time excessively.[14]

Type: Selecting Appropriate Exercise Modalities

The type component encompasses the specific activities you choose to perform, with effective programs typically incorporating multiple exercise modalities. The three primary categories include aerobic (cardiovascular) exercise, resistance (strength) training, and flexibility work, each providing distinct physiological benefits.

[2]

Aerobic exercises elevate heart rate and breathing for sustained periods, strengthening the cardiovascular system and enhancing endurance. Common modalities include walking, jogging, running, cycling, swimming, rowing, dancing, and group fitness classes. The beauty of aerobic exercise lies in its versatility—activities can be modified to suit individual preferences, physical limitations, and environmental constraints. Research indicates that varying aerobic activities prevents boredom and reduces overuse injury risk, making exercise rotation a strategic approach for long-term adherence.[8]

Resistance training builds muscular strength and endurance through exercises that challenge muscles against external resistance. This category encompasses free weights (dumbbells, barbells), weight machines, resistance bands, hydraulic equipment, and bodyweight exercises like push-ups, pull-ups, and squats. Strength training provides benefits extending far beyond muscle building—it enhances bone density, improves metabolic rate, supports joint health, and reduces age-related muscle loss (sarcopenia).

Flexibility training maintains and improves range of motion through stretching exercises, yoga, Pilates, and similar modalities. While often undervalued, flexibility work prevents injuries, reduces muscle tension, improves posture, and enhances functional movement patterns essential for daily activities. Static stretching (holding positions) and dynamic stretching (controlled movements through full range of motion) serve different purposes—dynamic stretches work well in warm-ups, while static stretches optimize cool-down periods.[2]

For older adults and those at fall risk[15], a fourth category—balance training—becomes critically important. Activities like tai chi, standing on one foot, heel-to-toe walking, and specific balance exercises reduce fall risk and maintain functional independence. Research demonstrates that incorporating balance training two to three times per week significantly decreases fall incidents among older populations.

Applying the FITT Principle: Practical Implementation

Creating Your Baseline FITT Program

Successful implementation[16] begins with honest self-assessment of your current fitness level, available time, resources, and specific goals. Beginners might start with a conservative program: three 20-30 minute sessions of moderate-intensity walking per week (aerobic component), supplemented by two resistance training sessions using bodyweight exercises or light weights targeting major muscle groups. This foundational approach allows your body to adapt without overwhelming your cardiovascular system[17] or musculoskeletal structures.[2]

A sample beginner FITT program might look like this:

Aerobic Component:

- Frequency: 3-4 days per week

- Intensity: Moderate (60-70% max heart rate or RPE 5-6)

- Time: 20-30 minutes per session

- Type: Walking, cycling, or swimming

Resistance Component:

- Frequency: 2 days per week (non-consecutive days)

- Intensity: Light to moderate (60-70% 1-RM or 12-15 repetitions)

- Time: 30-40 minutes (8-10 exercises, 2 sets each)

- Type: Bodyweight exercises progressing to light dumbbells or machines

Flexibility Component:

- Frequency: Daily or at minimum after each workout

- Intensity: Gentle stretch to point of mild tension

- Time: 10-15 minutes (30-60 seconds per major muscle group)

- Type: Static stretching during cool-down

Progressive Overload: The Key to Continued Improvement

The principle of progressive overload[18] states that physiological adaptations occur only when the body faces demands exceeding its current capacity. Without progressive increases in training stress, fitness plateaus inevitably occur. The FITT principle framework provides four distinct pathways for progressive overload, allowing strategic manipulation of training variables as your fitness improves.[9]

Research suggests increasing any single FITT component by no more than 10% per week to allow gradual adaptation while minimizing injury risk. For example, if you currently walk 30 minutes per session, increasing to 33 minutes the following week represents appropriate progression. Alternatively, you might add an additional weekly session (increasing frequency), slightly increase your walking pace (increasing intensity), or incorporate intervals of faster walking (modifying type while increasing intensity).[19]

The periodization concept—cycling through different training phases emphasizing different fitness components—prevents plateaus and maintains motivation. A periodized approach might emphasize building endurance for 4-6 weeks (longer duration at moderate intensity), followed by a phase focusing on intensity (shorter, more vigorous sessions), then a strength-building phase (increased resistance training). This systematic variation challenges your body through diverse stimuli, promoting comprehensive fitness development.

FITT Principle Modifications for Special Populations

Older Adults and Seniors

Older adults[20] benefit enormously from structured exercise following FITT principles, with modifications addressing age-related physiological changes and increased chronic disease prevalence. The American College of Sports Medicine recommends older adults engage in 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity weekly (or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity), supplemented by resistance training at least twice weekly, flexibility work at least twice weekly, and balance training two to three times weekly for those at fall risk.

[13]

Intensity modifications become particularly important for this population. Starting at the lower end of target heart rate zones (50-60% maximum heart rate) allows safe initiation, with gradual progression as tolerance improves. The perceived exertion scale proves especially valuable for older adults taking medications that alter heart rate responses, such as beta-blockers.[10]

Exercise type selection should emphasize low-impact activities minimizing orthopedic stress—walking, swimming, stationary cycling, and water aerobics represent excellent choices. Resistance training should initially utilize machines providing stability support before progressing to free weights as balance and strength improve. Research demonstrates that even frail older adults can safely participate in appropriately modified resistance training programs, with significant improvements in strength, functional capacity, and quality of life.

Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes

For individuals with type 2 diabetes, exercise represents a cornerstone intervention[21] rivaling pharmacological treatments in effectiveness. The FITT prescription for this population emphasizes both aerobic and resistance training, as each modality provides complementary metabolic benefits. Aerobic exercise enhances insulin sensitivity and glucose uptake through insulin-independent pathways, while resistance training increases muscle mass, which improves overall glucose disposal capacity.[21]

Recommended FITT parameters for individuals with type 2 diabetes include:

- Frequency: At least 3 days per week of aerobic exercise (ideally 5 days), plus 2-3 days of resistance training

- Intensity: Moderate to vigorous (50-85% maximum heart rate)

- Time: Minimum 150 minutes weekly of moderate-intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic exercise; resistance training sessions of 20-30 minutes

- Type: Walking, cycling, swimming, or other aerobic activities; resistance training targeting all major muscle groups

Special considerations include blood glucose monitoring before, during, and after exercise, particularly for insulin users; proper footwear to prevent diabetic foot complications; adequate hydration; and awareness of hypoglycemia symptoms. Exercise timing relative to medication administration and meals requires coordination with healthcare providers to optimize glycemic control while minimizing hypoglycemia risk.[22]

Individuals with Cardiovascular Conditions

Exercise prescription for individuals with hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure, or peripheral artery disease requires careful FITT principle modifications[23] based on disease severity and clinical status. For hypertension management, aerobic exercise takes primacy, with substantial blood pressure reductions (5-7 mmHg) documented following regular moderate-intensity training. Frequency should target most days of the week (5-7 days), with moderate intensity (40-60% maximum heart rate initially), for 30-60 minutes per session.[13]

Resistance training, once discouraged for hypertensive individuals, now receives recommendation at moderate intensity (60-80% 1-RM) for 2-3 days weekly, as research demonstrates safety and additional blood pressure benefits. However, heavy lifting and Valsalva maneuvers (holding breath during exertion) should be avoided due to excessive blood pressure spikes.[24]

Cardiac rehabilitation programs typically utilize supervised exercise with continuous ECG monitoring initially, progressively transitioning to independent community-based programs as cardiovascular stability and functional capacity improve. Pre-participation medical evaluation, including exercise stress testing, becomes essential for this population to identify exercise-induced arrhythmias, ischemia, or inappropriate blood pressure responses.[23]

Measuring and Monitoring Exercise Intensity

Heart Rate-Based Methods

Heart rate monitoring provides the most objective intensity measure, with several calculation methods available. The age-predicted maximum heart rate formula (220 – age) offers simplicity but significant individual variation. The Karvonen formula, or heart rate reserve (HRR) method, provides greater accuracy by incorporating resting heart rate: Target HR = [(Max HR – Resting HR) × Intensity %] + Resting HR.

For example, a 45-year-old with a resting heart rate of 80 bpm targeting 70% intensity would calculate: Maximum HR = 220 – 45 = 175 bpm; HRR = 175 – 80 = 95 bpm; Target HR = (95 × 0.70) + 80 = 146.5 bpm.[10]

Heart rate can be measured manually by palpating the radial artery at the wrist or carotid artery in the neck, counting beats for 15 seconds and multiplying by four, or through wearable technology like fitness trackers and heart rate monitors providing continuous real-time data. Modern devices offer the advantage of tracking heart rate zones throughout workouts, providing valuable feedback for maintaining appropriate intensity.[11]

Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE)

The RPE scale, developed by Swedish psychologist Gunnar Borg, ranges from 1 to 10 (or sometimes 6 to 20) and correlates remarkably well with physiological exertion markers. This subjective assessment considers breathing rate, muscle fatigue, sweating, and overall perceived effort. Research validates RPE as a reliable intensity indicator, particularly for populations where heart rate monitoring proves impractical or unreliable.

A practical RPE guide for exercise intensity:

- Very Light (RPE 1-2): Normal breathing, easy conversation, minimal exertion

- Light (RPE 3-4): Slight breathing increase, comfortable conversation, sustainable indefinitely

- Moderate (RPE 5-6): Heavier breathing, conversation possible but requiring effort, sustainable for extended periods

- Vigorous (RPE 7-8): Difficult to speak in complete sentences, breathing hard, sustainable for shorter durations

- Very Hard (RPE 9): Extremely difficult to talk, near-maximal breathing, sustainable only briefly

- Maximum (RPE 10): Cannot maintain, completely breathless, unsustainable

The “talk test” provides a simplified version of RPE assessment—during moderate-intensity exercise, you should be able to talk but not sing, while vigorous-intensity exercise makes conversation difficult.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

The “Too Much, Too Soon” Trap

Perhaps the most prevalent error among exercise initiates involves excessive enthusiasm manifesting as too frequent, too intense, or too prolonged initial workouts. This approach overwhelms the body’s adaptive capacity[16], leading to excessive muscle soreness, injury, burnout, and ultimately, program abandonment. Research indicates that individuals starting with conservative programs and gradually progressing demonstrate significantly better long-term adherence compared to those beginning aggressively.[4]

The 10% rule provides practical guidance—increase any single FITT component by no more than 10% per week. If you walk 20 minutes daily, increasing to 22 minutes the following week represents appropriate progression. Listen to your body’s signals—persistent muscle soreness extending beyond 2-3 days, joint pain, extreme fatigue, or decreased motivation suggest excessive training stress requiring program modification.[19]

Neglecting Rest and Recovery

Many exercisers mistakenly equate rest days with laziness, failing to recognize that physiological adaptations occur during recovery periods, not during exercise itself. Muscle strengthening, cardiovascular improvements, and metabolic adaptations require adequate recovery time between training sessions. The FITT principle inherently incorporates recovery through frequency recommendations—resistance training should never target identical muscle groups on consecutive days.[2]

Active recovery—engaging in very light activity like easy walking, gentle stretching, or leisure cycling on rest days—can enhance recovery by promoting blood flow to healing tissues without imposing significant training stress. Inadequate recovery manifests through plateaued performance, persistent fatigue, decreased motivation, irritability, disrupted sleep, and increased injury susceptibility.[4]

Insufficient Exercise Variety

Performing identical workouts repeatedly creates multiple problems: boredom-induced motivation decline, plateaued fitness improvements due to physiological adaptation, and increased overuse injury risk from repetitive stress on identical tissues. The FITT principle’s Type component specifically addresses this issue by encouraging exercise variation.[2]

Strategic variation can occur across multiple dimensions—alternating between different aerobic activities (cycling one day, swimming another, walking a third), modifying resistance training exercises targeting the same muscle groups (alternating between machines, free weights, and bodyweight exercises), and periodically adjusting intensity and duration patterns. This variation maintains physical and psychological freshness while promoting comprehensive fitness development.[5]

Ignoring Proper Form and Technique

Sacrificing exercise form to lift heavier weights, complete more repetitions, or move faster represents a dangerous mistake undermining training effectiveness while dramatically increasing injury risk. Proper technique[25] ensures targeted muscles receive appropriate stimulus, protects joints and connective tissues from excessive stress, and promotes safe movement patterns.[4]

For resistance training, the principle “quality over quantity” applies absolutely—performing 8 repetitions with excellent form generates superior results to 12 repetitions with compromised technique. Consider working with a qualified personal trainer or physical therapist initially to learn proper exercise mechanics, particularly for complex movements like squats, deadlifts, and overhead presses.

Strategies for Long-Term Exercise Adherence

Setting SMART Goals

Goal-setting profoundly influences exercise adherence, but goal quality matters tremendously. SMART goals—Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound—provide clear direction and enable progress tracking. Rather than vague aspirations like “get in shape,” SMART goals specify concrete targets: “Walk 30 minutes at moderate intensity five days per week for the next eight weeks” or “Increase leg press weight from 100 to 130 pounds within three months.”[26]

Research demonstrates that individuals with written goals[27] demonstrate significantly better adherence than those with unwritten aspirations. Further, combining long-term outcome goals (ultimate achievement targets) with short-term process goals (specific behaviors to perform) optimizes motivation and adherence. The process goals (following your FITT plan consistently) remain within your control, while outcome goals (weight loss, strength gains, race completion) depend partially on factors beyond direct control.[16]

Tracking Progress and Celebrating Milestones

Monitoring exercise sessions[28]—recording dates, durations, distances, weights lifted, and subjective experiences—provides tangible evidence of progress, enhances motivation, and identifies patterns requiring adjustment. Numerous tools facilitate tracking: traditional paper logs, smartphone apps, fitness trackers, and simple calendar notations all work effectively, with the best method being whichever you’ll use consistently.[16]

Celebrating achievements, particularly non-scale victories like improved stamina, increased strength, better sleep, enhanced mood, or reaching duration/distance milestones, reinforces positive behavior and maintains motivation through inevitable plateaus. Reward milestones with non-food treats aligned with your fitness journey—new workout clothes, fitness equipment, massage sessions, or recreational outings.[27]

Building Social Support Systems

Social support[29] dramatically improves exercise adherence through multiple mechanisms: accountability (less likely to skip when others expect you), motivation (encouragement during challenging periods), practical assistance (workout partners, childcare assistance), and enjoyment (social interaction makes exercise more pleasant). Research identifies both emotional support (empathy, encouragement) and practical support (exercising together, sharing transportation) as beneficial for adherence.[30]

Strategies for building exercise-related social support include joining group fitness classes, finding workout partners with similar goals and schedules, participating in walking or running clubs, engaging with online fitness communities, or hiring a personal trainer providing structured support. Family involvement proves particularly valuable—when family members support and participate in physical activity, adherence rates increase substantially.[27]

Creating Implementation Intentions

Implementation intentions—specific “if-then” plans specifying when, where, and how you’ll exercise—dramatically increase adherence by automating decision-making and reducing friction. Rather than vague intentions (“I’ll exercise this week”), implementation intentions create concrete action triggers: “If it’s Monday, Wednesday, or Friday at 6:30 AM, then I’ll walk 30 minutes around my neighborhood before breakfast.”[27]

This specificity bypasses the motivation bottleneck—rather than deciding whether to exercise each day, you simply execute the predetermined plan. Research demonstrates that individuals with implementation intentions achieve significantly higher adherence rates than those with equally strong intentions but no specific action plans.

Integrating the FITT Principle with Other Health Behaviors

Exercise effectiveness amplifies when integrated with complementary health behaviors, particularly nutrition, sleep, and stress management. Adequate protein intake (1.2-2.0 grams per kilogram body weight for individuals engaged in resistance training) supports muscle recovery and growth. Proper hydration maintains performance and facilitates physiological adaptations, with recommendations suggesting drinking before you feel thirsty and replacing fluids lost through sweat.[4]

Sleep profoundly influences exercise recovery, performance, and adherence—inadequate sleep impairs muscle recovery, decreases motivation, reduces exercise capacity, and increases injury risk. Most adults require 7-9 hours nightly, with physically active individuals potentially needing additional sleep to support training adaptations.[16]

Stress management deserves particular attention, as exercise itself represents a form of beneficial stress (eustress) that, when combined with excessive psychological stress, can overwhelm recovery capacity. Paradoxically, moderate exercise reduces psychological stress and anxiety, creating a virtuous cycle when managed appropriately but potentially exacerbating stress when overdone.[31]

The Role of Professional Guidance

While the FITT principle provides a solid framework for independent program design, professional guidance from qualified exercise professionals—certified personal trainers, clinical exercise physiologists, or physical therapists—can dramatically accelerate progress while reducing injury risk. Professionals provide personalized program design considering your medical history, current fitness level, biomechanical limitations, and specific goals.[4]

Medical consultation before beginning exercise programs becomes particularly important for individuals over 40, those with known chronic diseases (cardiovascular disease, diabetes, arthritis, respiratory conditions), individuals experiencing concerning symptoms (chest pain, dizziness, shortness of breath), or those with strong family histories of premature cardiovascular disease. Pre-participation screening identifies contraindications to specific exercises and guides appropriate intensity limits.[13]

Physical therapists offer specialized expertise for individuals with musculoskeletal limitations, chronic pain conditions, or those recovering from injuries or surgery. They can modify FITT parameters to accommodate physical limitations while progressively advancing function. For older adults, physical therapy-guided programs prove particularly valuable for addressing balance deficits, gait abnormalities, and functional limitations.

Conclusion: Your Path Forward

The FITT principle provides a time-tested, evidence-based framework for transforming physical activity from sporadic, unstructured efforts into systematic programs delivering meaningful health improvements. By thoughtfully manipulating Frequency, Intensity, Time, and Type variables, you create progressive challenges that stimulate physiological adaptations while respecting your body’s need for gradual progression and adequate recovery.[2]

Success hinges not on perfection but on consistency—a moderate program followed reliably produces vastly superior outcomes to an optimal program abandoned due to excessive demands. Start where you are, progress gradually using the FITT framework, celebrate your improvements, and recognize that every session contributes to your long-term health regardless of how it compares to idealized standards.[30]

The journey toward improved fitness represents a lifetime commitment rather than a temporary project. The FITT principle adapts alongside your evolving capabilities, providing structure through every phase—from tentative beginnings through periods of rapid improvement, across inevitable plateaus, and during the gradual modifications that aging requires. By embracing this flexible yet structured approach, you invest in functional independence, disease prevention, enhanced quality of life, and the profound satisfaction of caring for the remarkable vehicle that carries you through life.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. How often should I exercise each week as a beginner?

For beginners, starting with three to four exercise sessions per week provides an excellent balance between creating sufficient training stimulus and allowing adequate recovery time. This frequency should include two to three days of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise (walking, cycling, swimming) lasting 20-30 minutes each, plus two days of resistance training targeting major muscle groups. As your fitness improves over 4-6 weeks, you can gradually increase frequency to four to five sessions weekly, but always include at least one full rest day to allow your body to recover and adapt. Remember that consistency matters more than intensity when starting out—it’s better to maintain a moderate routine you can sustain rather than starting too aggressively and burning out within weeks.[32]

2. What’s the difference between moderate and vigorous exercise intensity, and how do I know which I’m doing?

Moderate-intensity exercise elevates your heart rate to approximately 50-70% of maximum (calculated as 220 minus your age) and corresponds to an activity level where you can speak in full sentences but cannot sing comfortably. Examples include brisk walking, leisurely cycling, or recreational swimming. Vigorous-intensity exercise pushes your heart rate to 70-85% of maximum and makes speaking in complete sentences difficult due to heavy breathing. Examples include jogging, running, fast cycling, or aerobic dance classes. The “talk test” provides a simple, practical method for gauging intensity without heart rate monitors—if you can talk comfortably, you’re at light intensity; if you can talk but not sing, you’re at moderate intensity; if speaking full sentences is difficult, you’re at vigorous intensity.[2]

3. Can I break up my exercise time throughout the day instead of doing it all at once?

Yes, absolutely! Research demonstrates that accumulating exercise in shorter bouts throughout the day produces similar cardiovascular and metabolic benefits to continuous sessions of equal total duration. For example, three 10-minute walking sessions spread across morning, lunch, and evening provide comparable benefits to one 30-minute continuous walk. This flexibility dramatically reduces barriers for individuals with limited time availability, busy schedules, or those who find long exercise sessions intimidating. The key is maintaining appropriate intensity during each bout—those 10-minute segments should still reach moderate intensity (where you’re breathing harder but can still talk) to count toward your weekly activity goals. This approach also provides an excellent strategy for gradually building exercise habits before progressing to longer continuous sessions.[14]

4. Should I do cardio or strength training first when I combine them in the same session?

The optimal sequence depends on your primary training goals, but general recommendations suggest performing the exercise type most important to your goals first when you’re freshest and have the most energy. If cardiovascular fitness or endurance represents your priority, complete cardio before strength training; if building strength or muscle mass is your main goal, perform resistance training first. For individuals focused on general fitness rather than specific performance goals, either sequence works effectively. However, many fitness professionals recommend completing resistance training first because proper form and technique become increasingly difficult as fatigue accumulates, and compromised form during strength exercises increases injury risk more dramatically than during steady-state cardio. A practical compromise involves alternating the sequence on different training days to ensure neither component consistently suffers from pre-exhaustion.[33]

5. How do I know if I’m experiencing normal muscle soreness or an actual injury?

Normal delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) typically appears 24-48 hours after exercise, particularly following new activities or increased intensity, and manifests as a dull, aching sensation distributed throughout the muscle belly that gradually improves within 2-3 days. This soreness should not prevent you from performing daily activities, though movements may feel stiff or uncomfortable. In contrast, injury-related pain often appears during or immediately after exercise, feels sharp or stabbing rather than dull, localizes to a specific point (especially near joints), worsens with specific movements, may cause swelling or bruising, and persists beyond 3-4 days without improvement. If you experience sharp pain, joint pain, pain that wakes you at night, pain that forces you to limp or alter your movement patterns, or discomfort that doesn’t improve with rest, stop exercising and consult a healthcare provider. Remember that some muscle soreness is normal and expected, especially when starting a new program, but pain is your body’s warning signal that should never be ignored.[34]

6. Will lifting weights make me bulky or overly muscular?

No, lifting weights will not automatically make you bulky or overly muscular, especially for women who have significantly lower testosterone levels than men—the primary hormone driving substantial muscle growth. Building large amounts of muscle mass requires years of consistent, progressive strength training combined with calculated caloric surplus and high protein intake, along with genetic predisposition. For most people, particularly those in caloric deficit for weight loss, strength training produces a lean, toned appearance by building moderate muscle while simultaneously reducing body fat percentage. The visible muscle definition often described as “toned” actually results from having moderate muscle mass with low body fat covering it, not from avoiding weights in favor of high-repetition, low-weight exercises. In fact, resistance training provides crucial benefits including increased metabolic rate, improved bone density, better functional strength for daily activities, enhanced joint stability, and reduced age-related muscle loss—benefits impossible to achieve through cardio alone.[35]

7. How long does it take to see results from a new exercise program?

The timeline for visible results varies significantly based on your starting point, program consistency, nutrition, sleep quality, genetics, and what type of “results” you’re measuring. However, some changes occur quite rapidly: improved mood and energy levels often appear within 1-2 weeks; enhanced cardiovascular endurance becomes noticeable within 2-4 weeks as activities that initially felt challenging become easier; strength gains emerge within 3-4 weeks, initially from neuromuscular adaptations (your nervous system learning to recruit muscle fibers more efficiently) before actual muscle growth begins; visible body composition changes typically require 6-8 weeks of consistent training, though this timeline extends significantly for those with less weight to lose. Remember that physiological improvements occur before visible changes—your heart becomes stronger, your muscles develop more mitochondria, your blood pressure improves, and your insulin sensitivity increases long before you see aesthetic changes in the mirror. Tracking non-scale victories like improved stamina, better sleep quality, enhanced mood, increased daily energy, and stronger performance metrics provides motivation during the weeks before visible transformation becomes apparent.[16]

8. Do I need to follow a structured program, or can I just go to the gym and do whatever I feel like?

While spontaneous exercise is better than no exercise, following a structured program produces dramatically superior results compared to unplanned workouts. A well-designed program ensures progressive overload (gradually increasing demands on your body), balanced muscle development (avoiding strength imbalances that lead to injury), appropriate exercise variety (preventing overuse injuries and boredom), adequate recovery time (allowing physiological adaptations to occur), and systematic progression toward your specific goals. Random workouts often lead to repeatedly training the same muscle groups while neglecting others, performing exercises at inappropriate intensities, inadequate recovery, and lack of progressive challenge resulting in fitness plateaus. You don’t necessarily need an expensive personal trainer—numerous evidence-based programs exist online and in fitness apps designed for various experience levels and goals. The key elements are having a plan that specifies which exercises to perform, how many sets and repetitions, what intensity to use, and how to progress over time.[36]

9. Should I exercise if I’m feeling sore from my previous workout?

Yes, you can and often should exercise with mild to moderate muscle soreness, but you should modify your activity appropriately. If you’re experiencing typical DOMS (delayed onset muscle soreness) that feels like a dull ache distributed throughout the muscle, engaging in light activity actually accelerates recovery by increasing blood flow to the affected tissues—a concept called active recovery. However, you should avoid intensely training the same muscle groups that are currently sore; instead, focus on different muscle groups or perform low-intensity cardiovascular exercise like easy walking, leisure cycling, or swimming. For example, if your legs are sore from squats and lunges, that’s an excellent day to train your upper body or perform gentle cardio. Listen to your body’s signals—if the soreness is so severe that it alters your movement patterns, limits your range of motion significantly, or hasn’t improved at all after 3-4 days, take additional rest rather than pushing through. Remember that consistent soreness after every workout may indicate inadequate recovery, excessive training volume, or insufficient nutrition, warranting program modifications.[37]

10. What should I eat before and after exercise to maximize my results?

Pre-exercise nutrition should provide easily digestible energy without causing gastrointestinal distress during your workout. For workouts lasting less than 60 minutes, eating isn’t mandatory if you’ve had a regular meal within 3-4 hours; however, if you’re exercising first thing in the morning or several hours after your last meal, consuming a light snack 30-60 minutes beforehand can improve performance. Ideal pre-workout snacks combine easily digestible carbohydrates with small amounts of protein: a banana with a tablespoon of peanut butter, Greek yogurt with berries, or half a turkey sandwich. Post-exercise nutrition becomes more critical, particularly after resistance training, as this represents your body’s optimal window for replenishing glycogen stores and providing amino acids for muscle repair. Aim to consume a meal or snack within 60-90 minutes after exercise that combines carbohydrates (to replenish energy stores) with 20-30 grams of high-quality protein (to support muscle recovery and growth): chicken with rice and vegetables, a protein smoothie with fruit, eggs with whole grain toast, or Greek yogurt with granola. Hydration deserves equal attention—drink water before you feel thirsty during exercise, and replace approximately 16-24 ounces of fluid for every pound lost during your workout.[38]

11. How do I stay motivated and avoid quitting my exercise program?

Long-term exercise adherence relies less on motivation (which naturally fluctuates) and more on building sustainable systems, habits, and support structures. The most effective strategies include setting specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART) goals rather than vague aspirations; tracking your workouts in a journal or app to provide tangible evidence of progress; celebrating non-scale victories like improved energy, better sleep, enhanced mood, or strength gains; establishing implementation intentions by specifying exactly when, where, and how you’ll exercise (“If it’s Monday at 6:00 AM, then I’ll go to the gym before work”); building social support through workout partners, group classes, online communities, or personal trainers who provide accountability; choosing activities you genuinely enjoy rather than forcing yourself through exercises you hate; starting with realistic, achievable goals and gradually progressing rather than overwhelming yourself; focusing on process goals (behaviors within your control like “complete three workouts this week”) rather than only outcome goals (results partially beyond your control like “lose 10 pounds”); and preparing for inevitable setbacks by having contingency plans for busy weeks, travel, illness, or motivational dips. Remember that a single missed workout doesn’t derail your progress—simply resume your routine the next day rather than abandoning it entirely.[39]

12. At what point should I consider working with a personal trainer or other fitness professional?

Several situations warrant professional guidance from certified personal trainers, clinical exercise physiologists, or physical therapists. Consider working with a professional if you’re completely new to exercise and feel overwhelmed by conflicting information; have specific performance goals (training for a race, athletic competition, or significant strength milestone); are recovering from injury or surgery; have chronic health conditions requiring exercise modifications (cardiovascular disease, diabetes, arthritis, osteoporosis); have hit a frustrating plateau despite consistent effort; want to learn proper exercise technique to prevent injuries; or simply want personalized program design and accountability to maximize results. Pre-participation medical consultation becomes particularly important before starting exercise programs if you’re over 40 years old, have known cardiovascular disease or diabetes, experience concerning symptoms (chest pain, dizziness, extreme shortness of breath), or have a strong family history of premature heart disease. Even a short-term investment in professional guidance—perhaps 4-8 sessions to learn proper form, establish a solid program foundation, and identify your specific limitations—can dramatically accelerate progress while reducing injury risk, ultimately proving more cost-effective than months of ineffective, unstructured training or time lost to preventable injuries.

References

- How To Use the FITT Principle. https://health.clevelandclinic.org/fitt-principle Accessed November 3, 2025

- study.com. https://study.com/academy/lesson/what-is-the-fitt-principle-definition-components-examples.html Accessed November 3, 2025

- 2. The FITT Principle – Ch. 5 – Fitness. https://open.online.uga.edu/fitness/chapter/fittprinciple/ Accessed November 3, 2025

- What is the FITT Formula?. https://www.americansportandfitness.com/blogs/fitness-blog/what-is-the-fitt-formula Accessed November 3, 2025

- FITT Principle for Cardio, Strength, Stretching & Injuries. https://stretchcoach.com/articles/fitt-principle/ Accessed November 3, 2025

- American Heart Association Recommendations for Physical Activity in Adults and Kids. https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/fitness/fitness-basics/aha-recs-for-physical-activity-in-adults Accessed November 3, 2025

- Physical Activity Guidelines. https://acsm.org/education-resources/trending-topics-resources/physical-activity-guidelines/ Accessed November 3, 2025

- The FITT Principle: Benefits & How to Use It. https://www.healthline.com/health/fitt-principle Accessed November 3, 2025

- study.com. https://study.com/academy/lesson/the-3-principles-of-training-overload-specificity-progression.html Accessed November 3, 2025

- Exercise intensity: How to measure it. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/fitness/in-depth/exercise-intensity/art-20046887 Accessed November 3, 2025

- Target Heart Rates Chart. https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/fitness/fitness-basics/target-heart-rates Accessed November 3, 2025

- Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) Scale. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/17450-rated-perceived-exertion-rpe-scale Accessed November 3, 2025

- Coming of Age: Considerations in the Prescription of Exercise for Older Adults. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4969034/ Accessed November 3, 2025

- The FITT Plan for Physical Activity. https://www.healthychildren.org/English/healthy-living/fitness/Pages/The-FITT-Plan-for-Physical-Activity.aspx Accessed November 3, 2025

- A Practice Guide for Physical Therapists Prescribing Physical Exercise for Older Adults. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38862112/ Accessed November 3, 2025

- Getting Started: Tips for Long-term Exercise Success. https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/fitness/getting-active/getting-started---tips-for-long-term-exercise-success Accessed November 3, 2025

- 10 Tips for Exercising Safely. https://www.health.harvard.edu/healthbeat/10-tips-for-exercising-safely Accessed November 3, 2025

- Progressive Loading. https://www.barbellmedicine.com/blog/progressive-loading/ Accessed November 3, 2025

- Progressive Overload Explained: Grow Muscle & Strength Today. https://blog.nasm.org/progressive-overload-explained Accessed November 3, 2025

- Physical activity guidelines for older adults. https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/exercise/physical-activity-guidelines-older-adults/ Accessed November 3, 2025

- Exercise and Type 2 Diabetes: The American College of Sports Medicine and the American Diabetes Association: joint position statement. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2992225/ Accessed November 3, 2025

- 403 Forbidden. https://www.teladochealth.com/library/article/the-fitt-principle-for-people-with-diabetes Accessed November 3, 2025

- Does Aerobic Exercise and the FITT Principle Fit into Stroke Recovery?. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4560458/ Accessed November 3, 2025

- F.I.T.T. for Resistance Training . https://www.healtheuniversity.ca/EN/CardiacCollege/Active/Resistance_Training/Pages/the-fitt-principle.aspx Accessed November 3, 2025

- Starting an Exercise Program - OrthoInfo. https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/staying-healthy/starting-an-exercise-program/ Accessed November 3, 2025

- How to Start Exercising: A Beginner's Guide to Working Out. https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/how-to-start-exercising Accessed November 3, 2025

- Having Trouble Sticking to Your Exercise Program? Stay Motivated With These 13 Exercise Adherence Strategies. https://appliedsportpsych.org/blog/2022/01/having-trouble-sticking-to-your-exercise-program-stay-motivated-with-these-13-exercise-adherence-strategies/ Accessed November 3, 2025

- Steps for Getting Started With Physical Activity | Healthy Weight and Growth. https://www.cdc.gov/healthy-weight-growth/physical-activity/getting-started.html Accessed November 3, 2025

- Increasing Motivation for Exercise Adherence. https://www.netafit.org/2018/04/increasing-motivation-for-exercise-adherence/ Accessed November 3, 2025

- The three components of motivation affect exercise adherence – Human Kinetics Canada. https://canada.humankinetics.com/blogs/excerpt/the-three-components-of-motivation-affect-exercise-adherence Accessed November 3, 2025

- What Is the FITT Principle and How Can You Benefit from It?. https://flo.health/menstrual-cycle/lifestyle/fitness-and-exercise/what-is-the-fitt Accessed November 3, 2025

- Fitness for Beginners: A Step-by-Step Guide. https://oakbendmedcenter.org/2024/01/10/fitness-for-beginners-a-step-by-step-guide/ Accessed November 3, 2025

- The Fitness Beginner’s Top Questions Answered. https://fitonapp.com/fitness/the-fitness-beginners-top-questions-answered/ Accessed November 3, 2025

- Personal Trainer FAQs: Addressing Common Client Concerns. https://insurefitness.com/personal-trainer/common-questions-and-how-to-answer-them/ Accessed November 3, 2025

- Top 12 Beginner Fitness Questions. https://www.msfitnesschallenge.org/top-12-beginner-fitness-questions/ Accessed November 3, 2025

- 18 Questions Every Fitness Beginner Asks. https://sweat.com/blogs/fitness/questions-every-fitness-beginner-asks Accessed November 3, 2025

- Frequently Asked Questions. https://thefitness.wiki/faq/ Accessed November 3, 2025

- 12 Questions New Clients Ask Personal Trainers. https://www.nfpt.com/blog/12-questions-new-clients-ask-personal-trainers Accessed November 3, 2025

- The Top 10 Questions Beginners Ask About Strength Training (Answered!) — Iron & Mettle San Francisco Gym. https://www.ironandmettlefitness.com/blog/2025/2/26/the-top-10-questions-beginners-ask-about-strength-training-answered Accessed November 3, 2025