Yes, you can have an increased risk of heart disease even with a normal BMI if you carry excess visceral fat around your midsection. People with too much belly fat face higher cardiovascular risks even when their body mass index falls within the healthy range[1], according to research from the American Heart Association.

This happens because visceral fat plays an active role in how the body functions[2], unlike the fat you can pinch under your skin. While some visceral fat protects your organs, too much creates problems for your heart and blood vessels.

Many people think a normal BMI means they’re safe from heart disease risks. But BMI only looks at height and weight, not where fat sits in your body. The location of fat matters more than most people realize.

Key Takeaways

- Excess visceral fat increases heart disease risk even when BMI appears normal and healthy

- Waist measurements provide better cardiovascular risk assessment than BMI alone

- Regular exercise and dietary changes can reduce dangerous visceral fat levels effectively

Why Visceral Fat Is a Unique Cardiovascular Risk

Visceral fat poses distinct health threats that BMI measurements cannot detect, creating hidden cardiovascular dangers through inflammatory processes and hormonal disruptions that directly affect heart health.

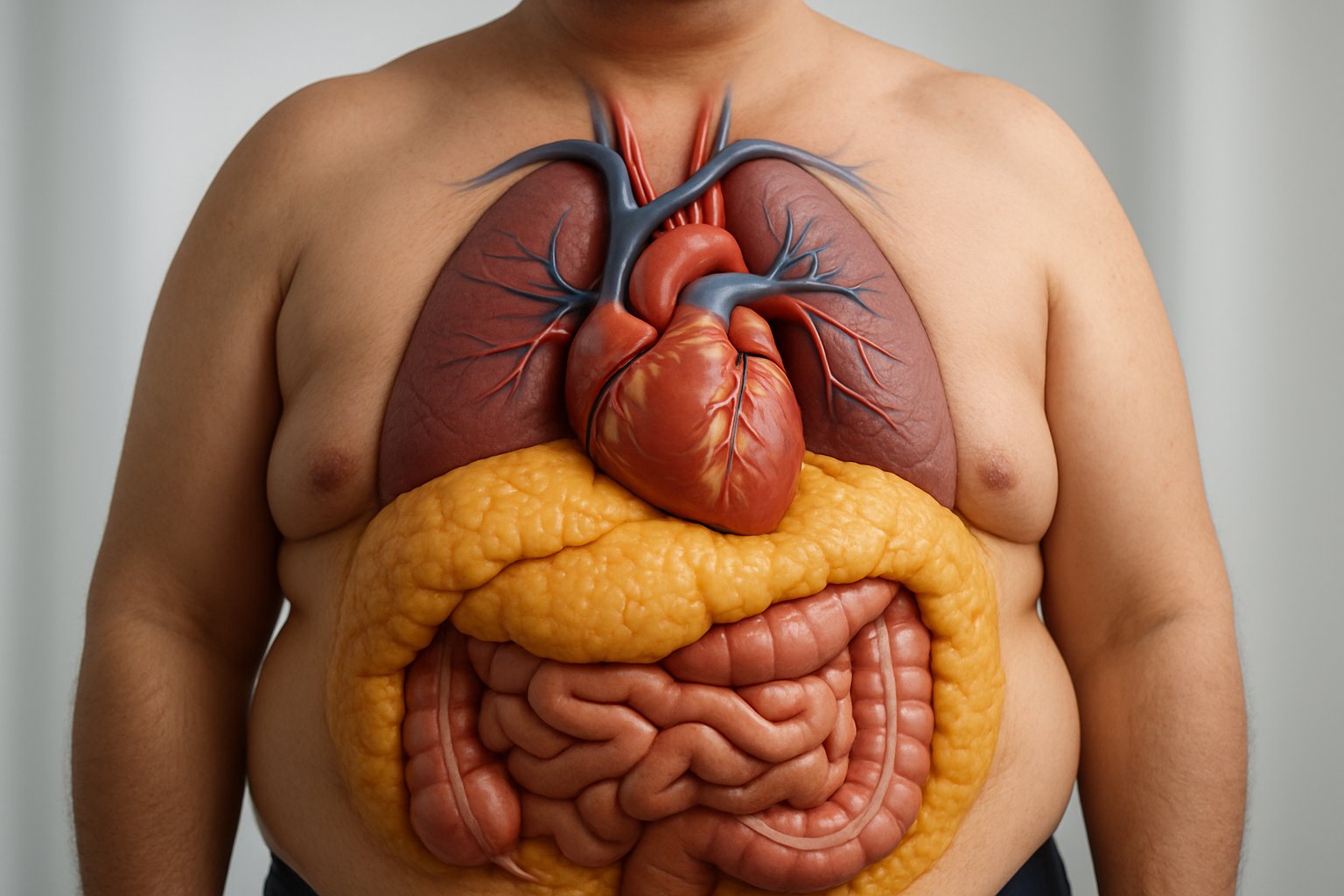

Difference Between Visceral and Subcutaneous Fat

Visceral fat surrounds internal organs in the abdomen, while subcutaneous fat sits just under the skin. These two types of adipose tissue behave very differently in the body.

Subcutaneous fat acts mainly as energy storage and insulation. It releases fewer harmful substances into the bloodstream.

Visceral adipose tissue is more cellular and vascular[3] than subcutaneous fat. It contains more immune cells and inflammatory cells that can damage blood vessels.

Key differences include:

- Location: Visceral around organs vs. subcutaneous under skin

- Blood flow: Visceral drains directly to liver via portal veins

- Cell activity: Visceral releases more hormones and inflammatory substances

- Metabolic impact: Visceral causes greater insulin resistance

The direct drainage of visceral fat to the liver means toxic substances reach this vital organ first. This creates a more dangerous pathway for cardiovascular disease development.

Why Visceral Fat Increases Cardiovascular Risk More Than BMI

BMI only measures total body weight relative to height. It cannot tell the difference between muscle, subcutaneous fat, and dangerous visceral fat.

People with healthy BMI ranges can still have elevated cardiovascular risks[1] if they carry excess visceral fat around their midsection.

Visceral fat releases free fatty acids directly into the portal circulation. These acids travel straight to the liver, causing:

- Increased cholesterol production

- Higher triglyceride levels

- Greater insulin resistance

- Elevated blood pressure

Normal-weight individuals with high visceral fat show similar cardiovascular risks to obese people. This explains why some thin people develop heart disease while some heavier people remain healthy.

Research shows that visceral fat contributes to faster aging of the heart and blood vessels[4], making it a stronger predictor of heart disease than overall body weight.

Role of Visceral Fat in Inflammation and Hormonal Changes

Visceral adipose tissue acts like an endocrine organ, producing hormones and inflammatory substances that damage cardiovascular health.

Inflammatory molecules released by visceral fat include:

- Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α)

- Interleukin-6 (IL-6)

- C-reactive protein

- Resistin

These substances create chronic low-grade inflammation throughout the body. The inflammation damages blood vessel walls and promotes atherosclerosis.

VAT has higher expression of stress hormone receptors[3], making it more sensitive to cortisol levels. Elevated cortisol increases visceral fat storage in a harmful cycle.

Hormonal disruptions from excess visceral fat include:

- Decreased adiponectin: Less protection for blood vessels

- Increased leptin: Higher inflammation and blood pressure

- Elevated cortisol: More fat storage around organs

- Insulin resistance: Higher blood sugar and diabetes risk

The combination of inflammation and hormonal changes creates multiple pathways to cardiovascular disease that BMI measurements completely miss.

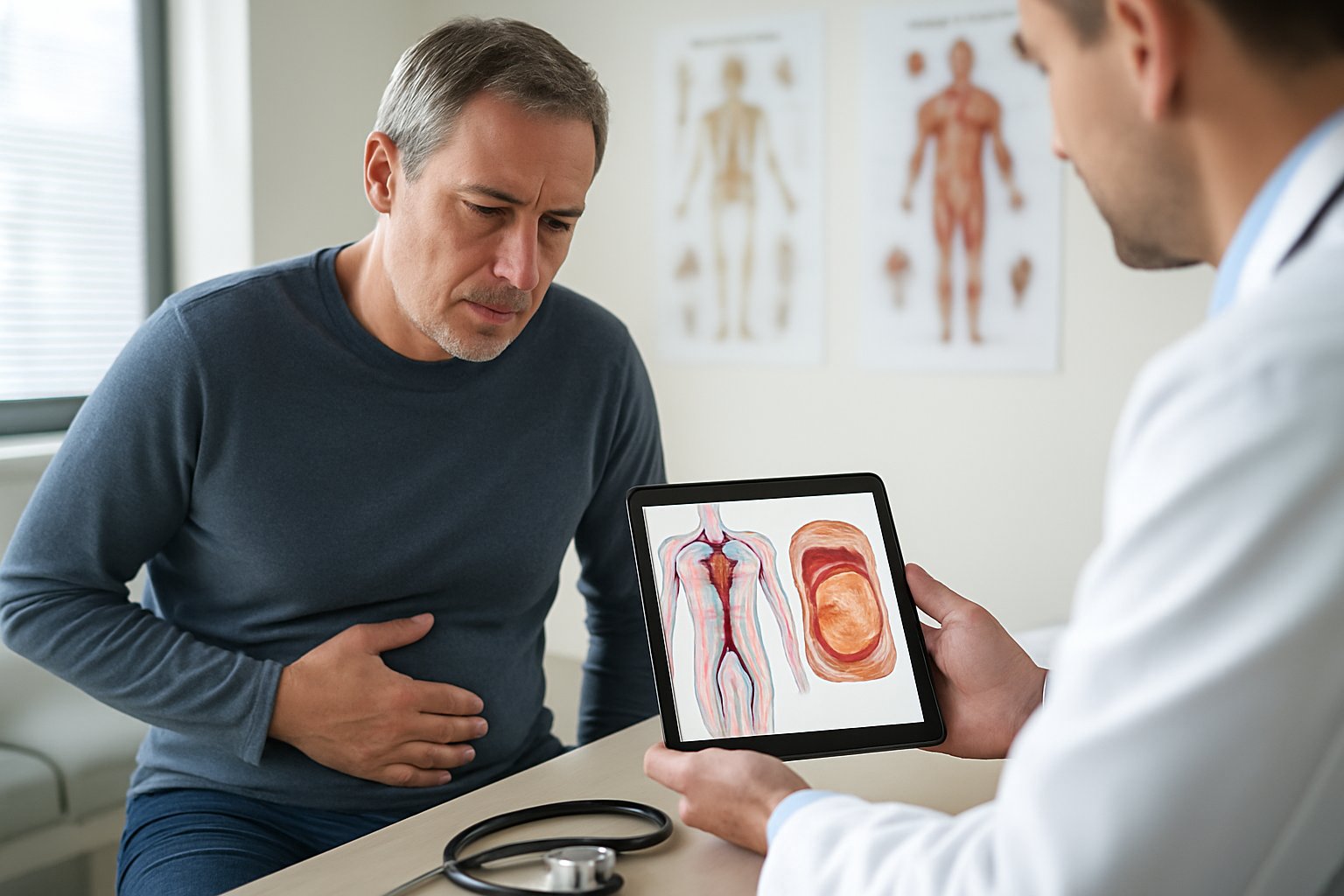

Normal BMI With High Visceral Fat: The Hidden Danger

Having a normal body mass index doesn’t guarantee protection from heart disease if visceral fat levels are high. This dangerous combination puts people at increased risk for heart disease even with healthy BMI numbers[1].

How You Can Have High Visceral Fat at a Healthy BMI

Body composition varies greatly between individuals with the same BMI. Two people can weigh the same but have completely different amounts of muscle, bone, and fat.

BMI only measures total body weight compared to height. It cannot tell the difference between muscle mass and fat mass. A person might have normal weight but carry excess fat around their organs.

Factors that contribute to high visceral fat at normal BMI:

- Age: Metabolism slows and fat shifts to the belly area

- Genetics: Some people store fat around organs more easily

- Hormones: Changes in estrogen and testosterone affect fat storage

- Lack of exercise: Inactive people lose muscle and gain abdominal fat

People who are “skinny fat” often fall into this category. They look thin but have low muscle mass and high body fat percentage.

Why BMI Alone Fails to Detect Cardiovascular Risk

BMI was created as a population health tool, not for individual risk assessment. It misses important details about where fat is stored in the body.

Visceral fat poses unique health risks[5] that BMI cannot detect. This type of fat wraps around vital organs and releases harmful chemicals into the bloodstream.

BMI limitations include:

- Cannot measure fat distribution

- Doesn’t account for muscle mass differences

- Ignores bone density variations

- Fails to detect metabolic health markers

Waist-to-hip ratio and waist circumference provide better insight into abdominal obesity. These measurements help identify people with dangerous visceral fat levels regardless of their total body weight.

Research on Cardiovascular Disease Risk in People With Normal BMI and High Visceral Fat

Studies show that abdominal fat measurement predicts cardiovascular death independent of BMI[1]. This means visceral fat creates cardiovascular risk even when body mass index appears healthy.

Research confirms that visceral fat is a clear health hazard[1] for heart disease. People with high abdominal fat face increased risk for several conditions.

Health risks include:

- Higher blood pressure

- Increased stroke risk

- Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- Type 2 diabetes development

- Elevated cholesterol levels

The American Heart Association recommends that doctors check both BMI and waist measurements during health visits. This combination provides a more complete picture of cardiovascular disease risk than BMI alone.

How Excess Visceral Fat Impacts the Heart and Blood Vessels

Visceral fat creates multiple pathways to cardiovascular problems by disrupting normal metabolic processes and increasing inflammation throughout the body. Excessive amounts of visceral fat contribute to faster aging of the heart and blood vessels[4], which becomes the biggest risk factor for heart disease.

Connection Between Visceral Fat and Heart Disease

Visceral adipose tissue directly increases the risk of cardiovascular disease through several mechanisms. Research shows that people with high levels of belly fat face elevated risks even when their BMI falls within normal ranges.

Too much weight around the middle can raise the risk for heart disease, whether a person’s body mass index is considered healthy or not[1]. This happens because visceral fat releases inflammatory substances directly into the bloodstream.

The fat surrounding internal organs produces cytokines and other inflammatory markers. These substances travel through the portal circulation to the liver and throughout the cardiovascular system.

Key cardiovascular impacts include:

- Increased coronary artery disease risk

- Higher rates of stroke

- Accelerated atherosclerosis development

- Greater likelihood of blood clots

Visceral Fat, Insulin Resistance, and Type 2 Diabetes

Visceral fat significantly impairs the body’s ability to process glucose effectively. The fat cells release free fatty acids that interfere with insulin signaling in muscle and liver tissues.

This creates a cycle where insulin resistance worsens over time. The pancreas produces more insulin to compensate, but cells become less responsive to the hormone’s effects.

Progression typically follows this pattern:

- Visceral fat accumulation begins

- Insulin resistance develops

- Blood sugar levels rise

- Type 2 diabetes emerges

People with insulin resistance face substantially higher cardiovascular disease risks. The condition affects blood vessel function and increases inflammation throughout the circulatory system.

Blood Pressure and Hypertension Risks

Excess visceral fat contributes to high blood pressure through multiple pathways. The fat tissue produces substances that affect kidney function and blood vessel constriction.

Visceral adipose tissue releases hormones that activate the renin-angiotensin system. This system controls blood pressure by regulating fluid retention and blood vessel diameter.

The inflammatory substances from belly fat also damage blood vessel walls. This damage makes arteries stiffer and less able to expand normally during heart contractions.

Blood pressure effects include:

- Systolic pressure increases – higher peak pressure during heartbeats

- Diastolic pressure elevation – increased resting pressure between beats

- Reduced arterial flexibility – stiffer blood vessels throughout the body

Impact on Cholesterol and Atherosclerosis

Visceral fat disrupts normal cholesterol metabolism and accelerates atherosclerosis development. The fat cells alter how the liver produces and processes different types of cholesterol.

People with excess belly fat typically show decreased HDL cholesterol levels. HDL cholesterol helps remove harmful cholesterol from artery walls and transport it back to the liver.

LDL cholesterol levels often increase with visceral fat accumulation. This “bad” cholesterol becomes more likely to form plaques inside blood vessel walls.

The inflammatory environment created by visceral fat makes cholesterol plaques more unstable. Unstable plaques can rupture and cause heart attacks or strokes.

Cholesterol pattern changes:

| Cholesterol Type | Typical Change | Cardiovascular Impact |

|---|---|---|

| HDL | Decreases | Reduced protection |

| LDL | Increases | Higher plaque risk |

| Triglycerides | Increases | Greater inflammation |

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease commonly develops alongside visceral fat accumulation. This condition further worsens cholesterol metabolism and increases cardiovascular disease risk.

Signs, Measurements, and How to Know Your Risk

Several key measurements can reveal visceral fat levels even when BMI appears normal. Waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio provide simple assessment tools, while body shape patterns indicate abdominal obesity risk.

Waist Circumference and Waist-to-Hip Ratio

Waist circumference serves as the most practical indicator of visceral fat accumulation. Men with waist measurements above 40 inches and women above 35 inches face increased cardiovascular risk regardless of their overall body size.

The measurement should be taken at the narrowest point between the ribs and hip bones. People should measure in the morning before eating for consistent results.

Waist-to-hip ratio adds another layer of assessment. This calculation divides waist circumference by hip circumference to determine fat distribution patterns.

Ratios above 0.90 for men and 0.85 for women indicate higher visceral fat levels. Even individuals with normal BMI can have concerning ratios that signal increased heart disease risk.

Body Shape and Abdominal Obesity Indicators

Apple-shaped body types typically carry more visceral fat than pear-shaped individuals. This pattern concentrates weight around the midsection rather than hips and thighs.

Abdominal obesity often appears as a firm, protruding belly rather than soft, pinchable fat. Visceral fat sits deep within the abdomen, creating a different texture than subcutaneous fat.

People may notice their pants fitting tighter around the waist while their arms and legs remain relatively thin. This combination suggests visceral fat accumulation despite normal overall weight.

Changes in belly fat distribution over time provide important clues. Gradual increases in waist size without corresponding weight gain often indicate growing visceral fat deposits.

Imaging and Advanced Testing: CT Scan and MRI

CT scan technology provides the most accurate visceral fat measurements available. These scans create detailed cross-sectional images that clearly distinguish between visceral and subcutaneous fat deposits.

Medical professionals can precisely calculate visceral fat area and volume using CT imaging. However, radiation exposure limits routine use of this testing method.

MRI offers similar accuracy without radiation risks. This imaging technique uses magnetic fields to create detailed pictures of internal fat distribution patterns.

Both methods remain expensive and typically reserved for research or specific medical situations. Most healthcare providers rely on simpler measurements for routine cardiovascular risk assessment.

DEXA scans represent a middle-ground option that provides body composition analysis with lower radiation exposure than CT scans.

Factors Contributing to Elevated Visceral Fat Despite a Normal BMI

Several key factors can cause visceral fat accumulation even when someone maintains a healthy weight on the scale. Genetic predisposition, hormonal shifts with aging, poor dietary choices, lack of exercise, and chronic stress all play important roles in where the body stores fat.

Genetics, Age, and Hormonal Influences

Genetic factors largely determine how the body distributes fat throughout life. Some people inherit genes that favor visceral fat storage over subcutaneous fat deposits.

Age-related hormonal changes significantly impact fat distribution patterns. Women experience increased visceral fat after menopause due to declining estrogen levels. Men see gradual increases in visceral fat as testosterone decreases with age.

Cortisol levels also influence where fat gets stored. People with naturally higher cortisol production tend to accumulate more visceral fat. This genetic variation explains why some individuals develop the metabolically obese, normal-weight phenotype[6].

Family history plays a major role. Children of parents with high visceral fat often show similar patterns even at normal weights.

Diet and Nutritional Triggers

Certain dietary patterns promote visceral fat storage regardless of total calorie intake. Refined carbohydrates and added sugars trigger insulin spikes that encourage fat storage in the abdominal cavity.

High fructose consumption from processed foods and sugary drinks directly contributes to visceral fat accumulation. The liver converts excess fructose into fat that gets stored around organs.

Trans fats and excessive saturated fats also promote visceral fat storage. These fats create inflammation that disrupts normal fat metabolism.

Alcohol consumption significantly increases visceral fat. Regular drinking raises cortisol levels and provides empty calories that the body preferentially stores as visceral fat.

Poor meal timing and irregular eating patterns can disrupt hormones that control fat storage. Late-night eating particularly promotes visceral fat accumulation.

Physical Inactivity and Chronic Stress

Sedentary lifestyles directly contribute to visceral fat accumulation even in people with normal BMIs. Lack of exercise reduces the body’s ability to use stored fat for energy.

Regular exercise helps reduce visceral fat more effectively than subcutaneous fat. High-intensity interval training (HIIT) shows particular effectiveness at targeting visceral fat deposits.

Chronic stress elevates cortisol levels for extended periods. High cortisol levels signal the body to store more fat around internal organs as a survival mechanism.

Sleep deprivation increases stress hormones and disrupts metabolism. Poor sleep quality contributes to both the obesity epidemic and visceral fat storage in normal-weight individuals.

Work-related stress and busy lifestyles often combine physical inactivity with elevated stress levels. This combination creates ideal conditions for visceral fat accumulation despite maintaining normal weight.

Reducing Visceral Fat and Minimizing Your Cardiovascular Risk

Targeted strategies focusing on diet, exercise, and lifestyle modifications can effectively reduce visceral fat levels and lower cardiovascular disease risk. These approaches work together to improve insulin sensitivity and promote sustainable weight loss.

Dietary Strategies for Visceral Fat Loss

A balanced diet rich in protein and fiber helps target visceral fat more effectively than general weight loss approaches. Increasing protein and fiber intake while eating consistent meals[7] supports metabolic health and reduces abdominal fat storage.

High-protein foods should make up 25-30% of daily calories. These include lean meats, fish, eggs, legumes, and Greek yogurt. Protein increases satiety and preserves muscle mass during weight loss.

Fiber-rich vegetables and fruits slow digestion and improve insulin sensitivity. Aim for 25-35 grams of fiber daily from sources like broccoli, berries, and whole grains.

Limiting refined carbohydrates and added sugars reduces visceral fat accumulation. Eating fatty foods and carbohydrates can make the body form more visceral fat[2]. Replace processed foods with whole food alternatives.

Meal timing matters for visceral fat loss. Eating regular meals every 3-4 hours prevents blood sugar spikes that promote fat storage around organs.

Role of Exercise: Cardio, HIIT, and Strength Training

Exercise directly targets visceral fat through multiple mechanisms that improve cardiovascular health. Different types of physical activity offer unique benefits for reducing abdominal fat and enhancing heart function.

Cardiovascular exercise burns calories and improves heart health. Moderate-intensity activities like brisk walking, swimming, or cycling for 150-300 minutes weekly effectively reduce visceral fat stores.

High-intensity interval training provides superior results for visceral fat loss compared to steady-state cardio. HIIT sessions alternate between intense bursts and recovery periods, typically lasting 15-30 minutes.

HIIT improves insulin sensitivity more effectively than traditional cardio. This enhanced insulin response helps the body process glucose better and reduces fat storage around organs.

Strength training builds lean muscle mass while burning visceral fat. Resistance exercises 2-3 times weekly increase metabolism and improve body composition. Compound movements like squats and deadlifts engage multiple muscle groups.

Combining all three exercise types maximizes visceral fat reduction and cardiovascular benefits.

Lifestyle Changes to Lower Abdominal Fat and Improve Heart Health

Stress management and sleep quality directly impact visceral fat accumulation and heart health. The stress hormone cortisol makes the body add to its store of visceral fat[2], creating a cycle that increases cardiovascular risk.

Quality sleep for 7-9 hours nightly regulates hormones that control hunger and fat storage. Poor sleep disrupts leptin and ghrelin levels, leading to increased appetite and visceral fat gain.

Stress reduction techniques like meditation, deep breathing, or yoga lower cortisol levels. Chronic stress elevates cortisol, which specifically promotes fat storage around internal organs.

Alcohol moderation supports visceral fat loss efforts. Excessive alcohol consumption increases belly fat and raises cardiovascular disease risk. Limit intake to one drink daily for women and two for men.

Smoking cessation improves cardiovascular health and reduces inflammation that contributes to visceral fat accumulation. Smoking damages blood vessels and increases heart disease risk independent of body weight.

Regular health monitoring through waist circumference measurements and blood pressure checks helps track progress and cardiovascular risk reduction.

Frequently Asked Questions

People with normal BMI can still carry dangerous amounts of visceral fat around their organs. Detection methods, health risks, and reduction strategies vary significantly based on individual factors and medical approaches.

How can one detect the presence of visceral fat without apparent obesity?

Waist-to-height ratio provides the most accurate assessment for people with normal BMI. A person should divide their waist measurement by their height to determine risk levels.

Waist-to-hip ratio offers another reliable method. Medical professionals measure the narrowest part of the waist and divide it by the widest part of the hips.

CT scans and MRI imaging provide the most precise measurements of visceral fat. These medical tests can detect visceral adipose tissue accurately[8] even when overall body weight appears normal.

Apple-shaped body types typically indicate higher visceral fat storage. People who carry weight around their midsection rather than hips and thighs face increased risk.

Are there specific health risks associated with carrying excess visceral fat?

Visceral fat acts as “active fat”[2] that directly influences body functions and hormone production. This type of fat releases inflammatory substances that damage blood vessels.

Cardiovascular disease risk increases significantly with excess visceral fat. People with too much belly fat face higher heart disease risk[1] even when their BMI falls within healthy ranges.

Type 2 diabetes develops more frequently in people with high visceral fat levels. The fat interferes with insulin function and blood sugar regulation.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease often accompanies visceral fat accumulation. This condition further increases cardiovascular disease risk and metabolic problems.

High blood pressure and abnormal cholesterol levels commonly occur with excess visceral fat. These factors combine to create metabolic syndrome.

What methods are most effective for reducing visceral fat?

Aerobic exercise combined with calorie reduction shows the highest success rates. Meeting federal guidelines of 150 minutes of physical activity per week[1] effectively reduces abdominal fat.

High-intensity interval training targets visceral fat more effectively than steady-state cardio. Short bursts of intense activity followed by rest periods maximize fat burning.

Strength training builds muscle mass and increases metabolic rate. Combining resistance exercises with cardio produces better results than either method alone.

Dietary changes focusing on whole foods and reduced processed foods help eliminate visceral fat. Limiting sugar and refined carbohydrates specifically targets abdominal fat storage.

Sleep quality and stress management play crucial roles in visceral fat reduction. Poor sleep and chronic stress increase cortisol levels that promote belly fat storage.

At what point does belly fat become a concern for heart disease?

Waist circumference measurements provide clear risk thresholds for both men and women. Men with waist measurements over 40 inches face increased cardiovascular risk.

Women show elevated risk when waist circumference exceeds 35 inches. These measurements indicate dangerous levels of visceral fat accumulation.

Waist-to-height ratio above 0.5 signals concern regardless of overall body weight. This measurement accounts for different body sizes and heights.

Medical professionals consider multiple factors beyond measurements alone. Family history, blood pressure, and cholesterol levels influence individual risk assessment.

How does gender affect the accumulation and loss of visceral fat?

Men typically accumulate visceral fat more readily than women during younger years. Testosterone influences fat distribution patterns that favor abdominal storage.

Women experience increased visceral fat accumulation after menopause. Declining estrogen levels shift fat storage from hips and thighs to the abdominal area.

Hormonal differences affect how quickly each gender can lose visceral fat. Men often see faster initial results from diet and exercise interventions.

Women may need longer time periods to achieve significant visceral fat reduction. Hormonal fluctuations throughout menstrual cycles can impact fat loss progress.

Pregnancy and childbirth can increase long-term visceral fat storage in women. Multiple pregnancies may compound this effect over time.

What strategies do cardiologists recommend to reduce belly fat and lower cardiovascular risk?

Regular cardiovascular screening helps monitor progress and adjust treatment plans. Cardiologists emphasize the importance of both BMI and abdominal measurements[1] during routine visits.

Lifestyle modifications combining diet and exercise receive primary recommendation. These approaches address multiple cardiovascular risk factors simultaneously.

Medication management for related conditions like diabetes and high blood pressure supports overall heart health. Controlling these factors reduces the impact of excess visceral fat.

Bariatric surgery consideration occurs for severe cases with multiple risk factors. Weight loss surgery has shown superior results[1] for reducing coronary artery disease risk compared to non-surgical weight loss.

Regular monitoring of inflammatory markers helps track cardiovascular risk reduction. Blood tests can measure improvements in metabolic health as visceral fat decreases.

References

- Too much belly fat, even for people with a healthy BMI, raises heart risks. https://www.heart.org/en/news/2021/04/22/too-much-belly-fat-even-for-people-with-a-healthy-bmi-raises-heart-risks Accessed October 20, 2025

- What Is Visceral Fat & How To Get Rid of It. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/24147-visceral-fat Accessed October 20, 2025

- Just a moment.... https://journals.lww.com/cardiologyinreview/fulltext/9900/visceral_adiposity_and_cardiometabolic_risk_.545.aspx Accessed October 20, 2025

- How Visceral Fat Increases Your Heart Disease Risk — Best Life. https://bestlifeonline.com/visceral-fat-heart-disease-risk/ Accessed October 20, 2025

- The truth about body fat? It's not all the same. https://mednews.uw.edu/news/truth-about-body-fat Accessed October 20, 2025

- Just a moment.... https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/physrev.00033.2011 Accessed October 20, 2025

- 6 Things You Should Do to Lose Visceral Fat, According to Dietitians. https://health.yahoo.com/wellness/nutrition/weight-loss/articles/6-things-lose-visceral-fat-170000555.html Accessed October 20, 2025

- Just a moment.... https://www.thelancet.com/journals/landia/article/PIIS2213-8587(19)30084-1/fulltext Accessed October 20, 2025